Guest post: Conservation champion Willard Wolfe enters Environmental Hall of Fame

Editor’s note: This post was contributed by noted writer, environmental historian, policy advisor and former MEC staff member Dave Dempsey.

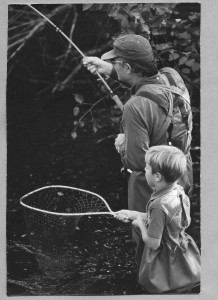

When dentist and fly fisherman Willard Wolfe saw the destruction of the trout streams he loved and the unbridled alteration of stream and lake habitat across Michigan, he didn’t get mad—he got to work.

Thanks to his vision and leadership, a strong draft bill was handed to activists who got it passed. Michigan had an historic lakes and streams protection law less than two years later. The 1972 Inland Lakes and Streams Act has saved countless Michigan water resources from damming, channelizing and filling.

For initiating, choosing, and chairing the statewide ad hoc committee that authored that law, and for a life of conservation activism, Wolfe was inducted into the Michigan Environmental Hall of Fame in May. A project of the Muskegon Environmental Research and Education Society (MERES), the Hall of Fame welcomed several other past and present advocates into its ranks in the same ceremony, held in the Gerald R. Ford Museum in Grand Rapids.

For those who knew Will, who died in 2011, the recognition was fitting. A gentleman with a quiet but firm persistence, he sought no reward for his conservation work—yet that work had lasting, statewide significance.

“His long-standing commitment to the joys of trout fishing on Michigan’s beautiful natural rivers made him a logical leader in the effort to provide effective controls,” MERES said in announcing Will’s induction. “This resulted in the Inland Lakes and Streams Act to protect the natural characteristics of our lakes and streams. Michigan led the nation in those years to provide adequate protections for these natural values.”

As is true of many conservationists, Will’s activism had roots in childhood. Growing up on Grosse Ile in the Detroit River, he was surrounded by nature. “As an Eagle Scout, he learned the names of the wildlife and many plants,” said his wife Joan. “As an enthusiastic small-boat builder and sailor, as well as just living on the river, he also learned to love wildlife. While his best friends hunted ducks and geese, he was content to just learn about them.”

After serving in the Army and graduating from Dartmouth College and the University of Detroit Dental School, Will set up practice in Grand Rapids and indulged his passion for angling. Living north of Grand Rapids near Rockford and fishing the Rogue River, he watched the stream turn multiple unnatural colors—red and blue among them—as a result of paper mill discharges. Co-founding the Rogue River Watershed Association in 1964, he helped put an end to the pollution.

Will was also president of the West Michigan Chapter of Trout Unlimited, helped found the Pere Marquette Watershed Council, was a board member of the Land Conservancy of West Michigan and the Michigan Land Use Institute (now the Groundwork Center for Resilient Communities), and chaired the Benzie County Conservation District.

But his greatest moment came with the drafting of the Inland Lakes and Streams Act. Appalled by the habitat destruction he saw, and faced with state natural resources officials who said their hands were tied, Will assembled a thoughtful group of conservation leaders, including a DNR liaison and an attorney-president of Trout Unlimited, to carefully craft the proposed law. No other state had a statute like it, but strong citizen support propelled it through the Michigan Legislature.

The lesson from Will’s work? To respect the knowledge of many people with all kinds of expertise. If you want to solve an environmental problem, gather people to discuss and work on solving those problems. Don’t try to do everything yourself.

It was an approach characteristic of Will, who fellow conservationist Jim Lockwood said never claimed credit for his accomplishments, deflecting it to others. “For Will,” Lockwood said, “environmental stewardship was a natural extension of one’s citizenship responsibilities.”

Will’s induction into the Hall of Fame joins him with wife Joan, founder of the West Michigan Environmental Action Council and the first woman to serve on (and eventually chair) the state Natural Resources Commission. She was inducted last year.

Also inducted this year were:

- Former Congressman John Dingell, author of numerous federal conservation laws;

- P.J. Hoffmaster, director of the Michigan Department of Conservation from 1934 to 1951 and architect of Michigan’s state park system;

- E. Genevieve Gillette, longtime volunteer state parks advocate and protector;

- Patricia McNinch, a physical education teacher at Mayville Elementary School who incorporates environmental values into her instruction;

- Kathy Evans, the Environmental Program Manager for the West Michigan Shoreline Regional Development Commission and a Muskegon area conservation leader.

Also recognized was the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community’s Sand Point Brownfield Remediation and Habitat Restoration Project. Polluted by industrial copper mining sand, the 33-acre property was listed as a brownfield site. Cleanup work began in 2002. Beginning in 2010, wildlife and biodiversity plantings were made to the site, providing habitat and recreation opportunities.

###

Written by Dave Dempsey.

Comments are closed.