Transportation funding: How’d we get here?

The package of transportation-funding bills Gov. Snyder signed earlier this month sets the stage for a ballot initiative with high stakes for drivers, transit riders and Michigan’s economy.

Voters in May will have their say on a proposed 1 percent increase in the state sales tax. Along with $300 million per year in new school funding, the proposal would raise about $1.2 billion a year for roads and at least $107 million annually for the Comprehensive Transportation Fund, which supports maintenance and upgrades to public transit and passenger rail. If approved, it would be the state’s first structural increase in funding for public transportation since 1987.

Like many Michiganders, we would have preferred a full solution from the Legislature, rather than facing the added cost, delay and uncertainty a ballot initiative adds to the process. But a ballot drive is what we’ve got, and MEC fully supports its passage.

In the run-up to the May vote, we’ll use this blog to take a close look at Michigan’s transportation system and to make our case that supporting that system in its entirety—not just roads and bridges—is essential to our state’s quality of life and economic competitiveness.

In this first installment of an occasional series, we’ll explore how Michigan arrived at such a desperate need for new transportation funding, and show we’re far from alone in that need.

How we got here

It only takes a few minutes behind the wheel on most Michigan roads to see how badly we need new transportation revenue. (Drive down Pine St. in Lansing from MEC’s offices to I-496. We dare you.)

What’s going on here? Why have the roads gotten so bad?

Here are some major reasons why our current approach to transportation funding has failed us:

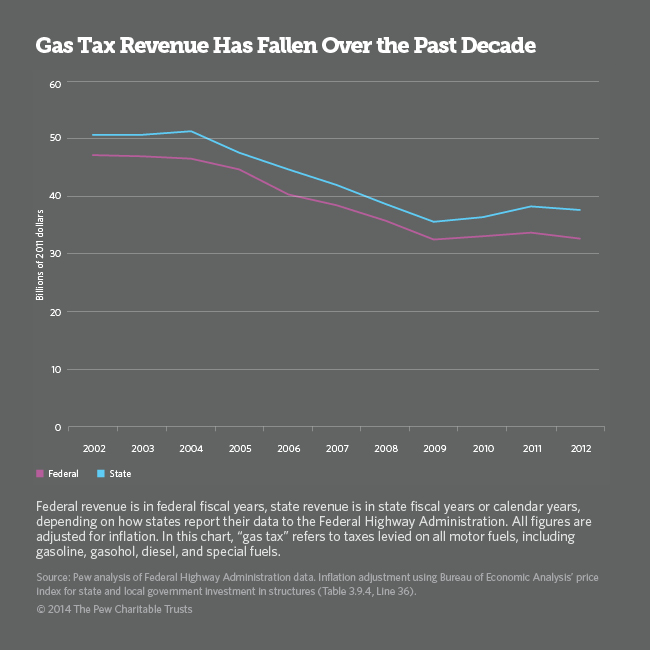

It lags behind inflation. Michigan’s flat tax rate on gasoline has increased from 4.5 cents per gallon in 1951 to today’s 19 cents, where it has stood since 1997, according to a 2012 Anderson Economic Group analysis for the Michigan Chamber of Commerce. But even as the tax rate has risen over the years, its buying power has dropped considerably. That’s because it has never been indexed to inflation, and has not kept up with the rising cost of maintaining our transportation infrastructure.

Decision making by Michigan road agencies has been based on the assumption that policymakers would do what’s needed to keep transportation revenue on pace with inflation. Instead, the gas tax has gone unchanged for nearly two decades while labor and material costs have steadily grown. We built new roads, but didn’t make the necessary investments to maintain them.

“If Michigan had instituted an inflation adjusting gas tax in 1997, rather than a flat-rate gas tax, drivers would be paying 27 cents per gallon now rather than the current 19 cents per gallon,” the Anderson report says. The 4.5 cents per gallon Michiganders paid in 1951 doesn’t sound like much, but it was the equivalent of 39 cents in 2011 dollars.

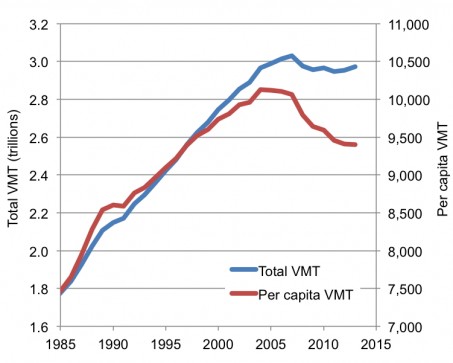

It doesn’t account for changing behaviors. For decades, the miles Americans drove each year rose steadily. But total vehicle miles traveled (VMT) has tapered off in recent years, and per-capita VMT has dropped more than 9 percent in the past decade. According to the University of Wisconsin’s State Smart Transportation Initiative, “this recent downward shift has had no clear, lasting connection to economic trends or gas prices.” Instead, it appears to be a sign of larger changes in the way Americans live.

Young people are leading those changes. You’ve probably heard all the relevant observations about the “Millennial” generation: They are choosing to live in urban areas where they can get around without a car. They’re deciding not to own a vehicle for environmental and economic reasons—or just to save the hassle. They’re opting to ride a bike or take convenient public transportation. As a result, the average VMT among 16-34-year-olds dropped by 23 percent between 2001 and 2009.

The environmental, social and health benefits of decreasing VMT are significant. However, fewer miles driven of course means less fuel purchased. And less fuel purchased means less tax revenue for transportation infrastructure.

It doesn’t have a good answer for more fuel-efficient cars. Federal mandates for gas-sipping vehicles—along with the rising popularity of hybrids and electric vehicles—are spurring innovation by automakers and driving down the amount of fuel it takes to get from A to B.

Again, that’s great news for the environment and our pocketbooks. But when we purchase less fuel, we pay less in fuel taxes. Developing a more sustainable funding mechanism is a necessity.

We’re not the only ones

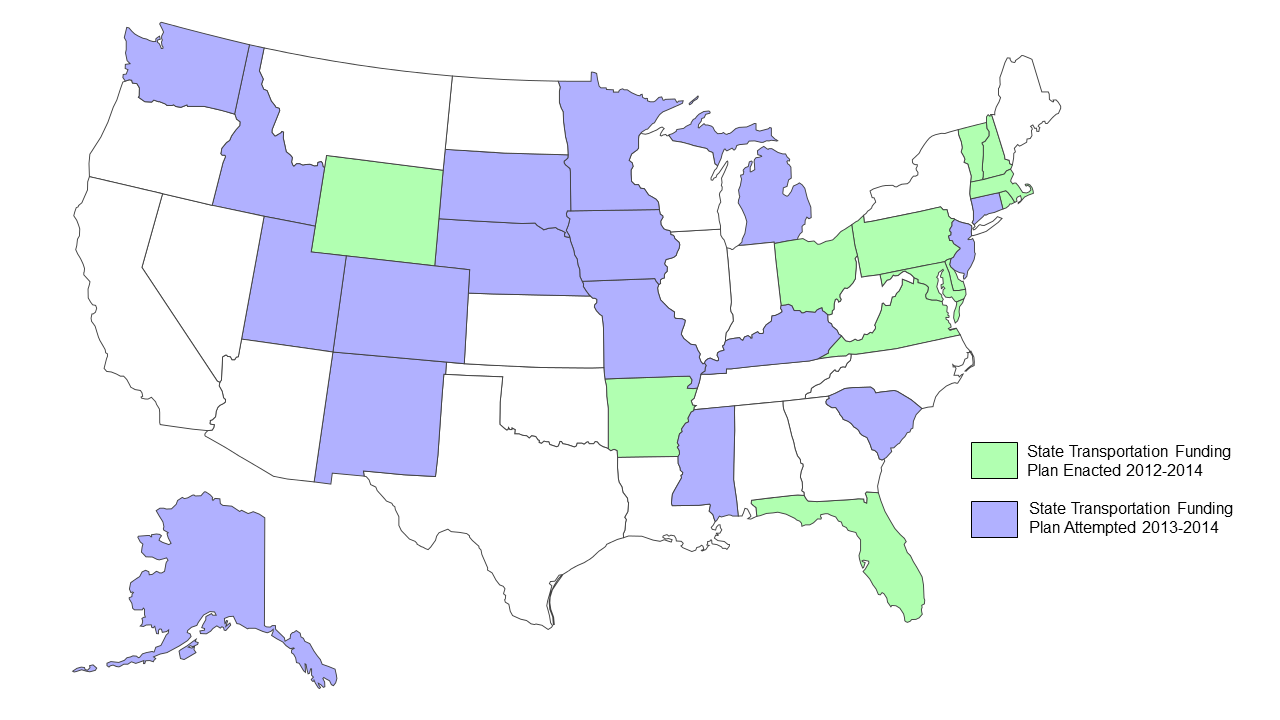

Over the past two years, 12 states have approved plans to increase funding for transportation. An additional 19 states (including Michigan) have attempted to increase funding in the past year, with most continuing to work on the issue. Solutions put forth by state leaders include indexing the gas tax to inflation, increasing the sales tax on fuel, increasing transportation-related fees and fines and more.

Bottom line: We are not in this alone. Even states with already-strong transportation systems—that’s you, Washington, Minnesota and Colorado—are looking at increasing funding. That makes it even more important for Michigan to pass a funding package to remain competitive for young talent and new business.

And it’s not only a state issue. The U.S. Highway Trust Fund, teetering on the brink of insolvency, is climbing the same uphill battle as Michigan’s transportation funding. Supported in large part by a fuel tax collected at the federal level, the HTF needs an increase of $30 billion per year to remain solvent and efficient. In Michigan, about 29 percent of total spending on transportation comes from the federal government—revenue that is now uncertain. If the last congressional session has taught us anything, it’s that we can’t wait for Congress to take action.

In part 2 of this series, we’ll explore how the new funding would impact various segments of Michigan’s transportation system.

-By Liz Treutel and Andy McGlashen

###

Photo courtesy John Eisenschenk via Flickr.

Comments are closed.

From a public policy standpoint we embrace “the best we can get” at our peril. I’m trying to understand the funding needs that were earlier tossed around - $1.8 - 2.0 Billion and how a “solution” of $1.3 Billion gets the job done. Were the earlier figures high?

OR are we asking the citizens to support higher taxes for a “solution” that will end up leaving our roads in worse shape 10 to 20 years down the road? If this is the case - we are missing a once in a generation chance to really improve our transit infrastructure - and will end up with a more cynical public because the policy makers let them down. And if the funding is not adequate there will be no incentive for the gerrymanders legislature to add addition funding.

Is the best we can do good enough? Have enough constituencies been bought off to win a May election? Interest groups have been brought on board, but I’m not sure the folks that really matter - the voters - will go along.