MEC and Tip of the Mitt highlight policy options worth pursuing in new UM fracking report

The University of Michigan last week released a report three years in the making that offers a comprehensive review of Michigan’s policy options regarding fracking for natural gas and oil.

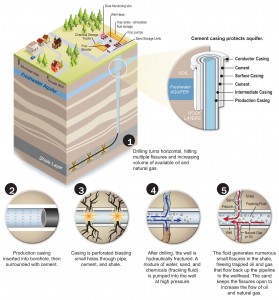

While fracking has been used for decades in Michigan, new techniques use far greater quantities of water and chemicals and pose greater risks to the environment and human health. Some recent fracking operations in Michigan have used as much as 21 million gallons of fresh water and more than 100,000 gallons of chemicals.

Many of the drilling sites are in pristine parts of Michigan known for their natural beauty, and it’s crucial to put the right policies on the books to protect these fragile areas that are the backbone of our tourism economy.

The Department of Environmental Quality updated its fracking regulations in March. The new rules are far from perfect, but they include some important provisions that reflect input from MEC and our allies during a public comment period on the draft rules. For instance, drilling companies now have to disclose what chemicals they’ll use before they inject them into the ground—not 60 days later, as previous rules allowed. The companies also are required to test water quality before drilling so they can be held accountable if contamination occurs.

The impressive research project by UM’s Graham Sustainability Institute enlisted experts, decision makers and key stakeholders to outline policy options. It does not recommend any specific course of action, but by presenting a menu of options, including the pros and cons of those options, it offers valuable input that can help Michigan regulators improve the state’s oversight of fracking. Importantly, it also notes that not enough study has been done to quantify the risks of high-volume hydraulic fracking on human health and the environment.

You can read the full report here. It’s a big document with a lot to chew on. Fortunately, MEC Policy Director James Clift and Grenetta Thomassey—a member of MEC’s board and program director for MEC member Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council—served on the advisory board for the study and are well-acquainted with the report and the issues involved.

Using that inside knowledge, James and Grenetta pulled out of the 174-page report some key areas that deserve special consideration by Michigan lawmakers and the Snyder administration. MEC supports each of the following policy options, which we’ve categorized by topic and identified by the number assigned to them in the report and the page on which they appear.

Public notice and involvement

2.3.3.2—Increase public notice. (Page 42.) Pursuing this policy option would expand public notification when the state proposes to lease oil and gas drilling rights on public land. The state now issues public notice in newspapers, sends announcements to local governments and posts information on the Department of Natural Resources website, among other measures. This policy option calls for notifying all adjacent landowners and posting announcements at the parcel itself, if the land is used for recreation. As the report notes, “Expanding public notice offers a relatively inexpensive way to increase transparency about potential state mineral rights leasing and ensure that affected parties have an opportunity to comment.”

2.3.3.3—Require DNR to prepare a responsiveness summary. (Page 42.) Current rules do not require the DNR to respond to public comments on state mineral leases. The basic idea here is to require the department to compile a summary of public comments received, how the department responded to public input and how that input influenced DNR’s decision about whether and how to lease the rights on that parcel. As the report notes, such a requirement would strengthen the state’s accountability to the public.

2.3.3.5—Increase public notice and comment when lessees submit an application to revise or reclassify a lease. (Page 43.) It makes sense that the state should be diligent in notifying the public not only when a company seeks to lease mineral rights on public land, but also when the company seeks to modify an existing lease. Those revisions could substantially change how the land is used—allowing drilling directly on the land, rather than with horizontal drilling from adjacent properties, for example—so it’s appropriate to increase public awareness of proposed changes. Not discussed in the report, but related: We believe the DNR should end the practice of leasing land before a formal assessment has been done. Currently, if the department does not have time to assess a nominated parcel, it will lease the land as “non-development,” which prevents access directly from the surface but may allow horizontal drilling from adjacent parcels. Many times drilling in the vicinity of recreational land can diminish its recreational value.

2.4.3.3—Require a public comment period with mandatory DEQ response. (Page 45.) The next two policy options have to do with the Department of Environmental Quality permits that drillers must obtain after securing leases with the DNR. Currently, there is no formal public comment process for these permits. This option calls for requiring a 30-day public comment period after a permit application is submitted, and could include a responsiveness summary like the one described above. “By inviting the public to comment on permit applications,” the report notes, “the DEQ may learn of important local considerations that should be factored into its decision making. At the same time, including the public in this decision making process may help relieve stress in affected communities as well as increase perceptions that DEQ is being transparent and treating the public fairly.”

2.4.3.4—Explicitly allow adversely affected parties to request a public hearing before a HVHF well permit is approved. (Page 46.) This option would allow local governments and residents to petition for a public meeting in the community where a drilling permit is sought, and would require the DEQ to hold such a meeting. The public could submit comments during the meeting or during a subsequent 15-day public input period, which the DEQ would be required to consider. The goal of this change would be to promote a community discussion regarding how development would occur and potential ways to minimize conflicting surface uses.

Water protection

3.2.1.2.3—Disallow any high-volume hydraulic fracturing (HVHF) operations within a cold-transitional stream. (Page 62.) Protecting cold-transitional streams is particularly important because they provide habitat for cold-water species but are very sensitive to changes in land use and stream flow. This policy option involves an outright ban on water withdrawals for fracking from these inherently fragile watersheds.

3.2.3.2—Update the scientific components of the Water Withdrawal Assessment Tool. (Page 66.) The Water Withdrawal Assessment Tool—which is used to ensure proposed large water withdrawals won’t have adverse impacts on nearby rivers and streams—represented the state-of-the-art in groundwater modeling when it was adopted in 2008. However, it is important to remember it was designed to serve as a screening tool and not to make final agency decisions within sensitive watersheds. In the context of high-volume fracking operations, the tool is only as good as the data we have in a particular area. Therefore, real-time monitoring of the impacts of water withdrawal would both protect cold-water habitat and provide valuable information for future decisions. In addition, improved models have been developed that could help the agency make better decisions if incorporated into the decision-making process.

Monitoring and regulation of wastewater disposal

3.3.5.2.2—Increase monitoring and reporting requirements. (Page 76.) Michigan’s regulations require a DEQ permit to dispose of the hazardous wastewater that is a byproduct of fracking, and that the waste be injected deep underground into stable rock formations where it can’t contaminate fresh water. As the report notes, “The presence of public concern over the volumes of wastewater being produced and disposed implies a need for greater transparency and expansion of wastewater disposal information.” This policy option calls for reporting to ensure that the volume of wastewater injected underground matches what drilling companies claim to have produced. It also notes that a publicly available database of wastewater injection data would be helpful for monitoring trends.

3.3.5.2.3—Obtain primary authority over Class II well oversight by the state. (Page 76.) Class II wells are the type of wells approved for disposal of fracking fluid. Currently, they are managed both by DEQ and the federal Environmental Protection Agency. This policy option would put Michigan in charge of regulating wastewater injection wells. Doing so would simplify reporting requirements for drillers while also improving oversight of wastewater disposal activities.

Financial assurance to protect taxpayers

4.4.2.3—Financial responsibility. (Page 102.) Michigan currently requires oil and gas companies to post bonds before drilling a well, to ensure that the companies can afford any necessary cleanup. However, the report notes, “Even the largest bonding amounts required by state law are insufficient to cover damages caused by a catastrophic release, which can amount to millions of dollars.” This policy option calls for requiring the companies to also purchase liability insurance, in addition to the bonds, to protect taxpayers from cleanup costs.

We hope to work with the Legislature and the administration in updating Michigan’s fracking regulations to include these common-sense measures.

The report identifies additional ways we can strengthen those regulations to protect our communities and natural resources. For instance, it cites a Maryland report calling for greater community involvement in preparing comprehensive plans to guide oil and gas development. Those plans could potentially provide better management of community impacts than our current well-by-well approach.

While the recent update to Michigan’s fracking regulations moved us in the right direction, there is still a great deal we can do to ensure that oil and gas drilling don’t harm our water resources, spoil our special places or put our health at risk.

The UM report and the priorities noted above provide a good place to start.

###

Top image: Tim Evanson via Flickr.

Fracking graphic: Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council.

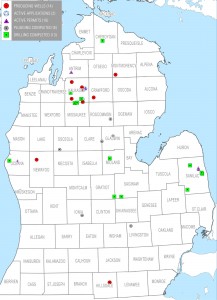

Map: Michigan Department of Environmental Quality.

Comments are closed.