Lawmakers should support reasonable protections for threatened bats

A plan to protect threatened bats from a deadly disease has drawn surprising criticism from a pair of lawmakers who say setting aside just one quarter of one percent of Michigan’s forested land area will have a “chilling effect” on the state’s logging and mining industries.

White-nose syndrome has devastated bat populations across the eastern United States, wiping out more than 90 percent of some colonies. The syndrome is caused by a fungus that infects hibernating bats.

In 2014 the disease was first spotted in Michigan on northern long-eared bats. The Department of Natural Resources expects to see populations of cave-dwelling bats decline by 50 percent to 90 percent over the next two years. In human terms, that’s like a disease that reduced the world’s population to the population of the United Kingdom. Since bats typically only have one or two pups a year, these populations will take many generations to rebuild. (One bright spot: Scientists last week announced that a common bacterium could help protect bats from the disease.)

To address the steep decline of these bats, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) has proposed to list the northern long-eared bat as threatened with a special rule that bars interference with the species unless certain exemptions are met.

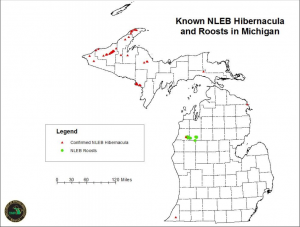

Among the exemptions are forest management and minimal tree removal projects, as long as certain conservation measures are followed. Those measures include avoiding areas within a quarter mile of a known and occupied hibernaculum (a cave or mine where bats hibernate in winter), avoiding cutting or destroying known and occupied roost trees and avoiding clear-cutting timber within a quarter mile of roost trees between June 1 and July 31 of each year.

FWS originally proposed listing northern long-eared bats as endangered, which would have barred any forest land in the state from being disturbed, since it is filled with potential roost sites. The DNR worked with FWS to draft the current rule to limit impacts to sustainable forest management, wildlife management, trail maintenance and other uses.

According to Sen. Tom Casperson (R-Escanaba) and Sen. Dave Robertson (R-Grand Blanc Township), one quarter of one percent of Michigan’s forests is too much land to protect a species from the very real threat of extinction. Both senators raised their concerns with how the rule would affect Michigan’s logging industry at the May 13 meeting of the Senate Natural Resources Committee, which Casperson chairs.

Casperson said he’d like to see an economic impact statement on the rule, since he thinks it sacrifices the livelihoods of Michigan families to protect a little bat. Since the rules wouldn’t have the same effect on low-impact uses like outdoor recreation, the senators said it feels like FWS is attacking the logging industry. If bats are so sensitive to logging that it can’t happen with a quarter mile of a roost tree (Casperson said 60 to 70 feet would be a more reasonable buffer), then they must also be affected by recreational activity, the senators contended. The meeting culminated with Robertson asking whether there are ways for Michigan to object to the rule, up to and including suing FWS. (Some environmental groups, meanwhile, are suing FWS to change the bat’s listing from threatened to endangered.)

Northern long-eared bats are a vital part of their ecosystem and are capable of eating more than 600 mosquitoes per hour. Michigan must at least keep in place the minimal protections in the current rule to help bat colonies recover from the staggering loss of life caused by white-nose syndrome. We hope lawmakers recognize the significant consequences if we do not protect these bats, and we encourage them to support the current rule, which provides reasonable and easy-to-implement protections while minimally affecting industry.

###

Photo of northern long-eared bat with white-nose syndrome courtesy USFWSmidwest via Flickr.

Comments are closed.